13 Reasons Why Wealth Holders Should Invest in the Solidarity Economy, Alongside Redistribution

As radical investment advisors, we often get questions like:

“Why should a wealth holder with a commitment to redistribution invest some of their assets?”

“Why might projects want investment capital and not only grants?”

One of the places these questions have arisen is in the Chordata Cohort. Our last cohort set up a $3M emergent flow fund and asked financial activists Aaron Tanaka, Jessica Norwood, and Anthony Chang to allocate that money as integrated capital. Nadav David and Jen Near then helped administrate some of that integrated capital. We recently invited Anthony, Nadav, and Jen into conversation with us, to glean learnings from this recent experience, and to share what we’ve learned over the years about the question of “why invest?”.

Let’s start with some basic premises that guide Chordata’s work:

- We invest in what we believe in. We only invest in tangible investments that center racial and economic justice, and we do NOT invest in the stock market.

- We believe in integrated capital, meaning that giving and investing are powerful and interconnected tools that can both be mobilized in support of social movements and the solidarity economy. Giving and investing are not two sides of a binary.

- We believe that wealth holders should use their surplus to both redistribute wealth as well as invest in ways that are reparative. We work with clients to develop an investment portfolio that includes both planning for the future and wealth redistribution. We then support people to build investment and redistribution strategies in relationship to those different time horizons.

- We apply the same principles and values to giving and to investing. Often with giving and investing, people are taught to hold two different sets of value systems. Someone’s giving may be beautifully aligned with racial justice values. But behind closed doors the investment thesis that money should make money off of money often reigns, and a wealth holder’s dollars might be invested in corporations that exploit communities of color. We seek to align our values and practices in giving and investing.

So if we hold to be true that giving is an essential part of redistributing resources, why then, also invest in the solidarity economy? Here are 13 reasons we came up with in conversation with each other.

1. Because a project or a movement group asks for it.

If you’re in consistent and meaningful relationships with partners, then partners will tell you what they need and why. If you can offer grants, and if groups say what’s best is grants, move a grant! If they ask for debt capital, either they’ve assessed that they can carry that debt because they imagine they’re going to have revenue in the future to pay it back, or they know they need it because they can use it to leverage other private and public funding, or some other reason. – Jen Near

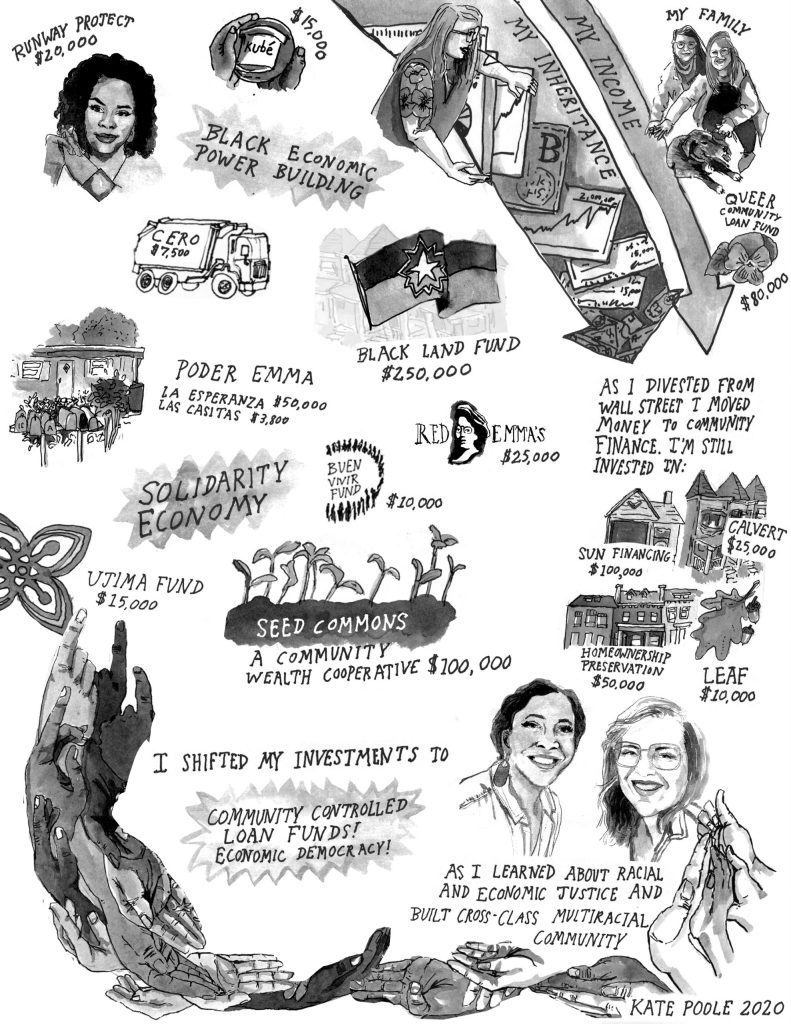

Some groups already have an existing relationship with debt, and they’re already used to financing projects in that way. They may usually get it from a CDFI or credit union. If they’re able to get this debt at 0 or 2% instead of the 4 or 6% from the financial institution, they have more space to do the work. – Kate Poole

2. If you have money that you’re saving for future use, you can put that money to work so that other people can build resources.

Frontline groups need capital, and sometimes wealth holders have already allocated their giving dollars. But the other 90% of wealth holder’s assets can also be put to work. Folks on the ground can use that money to build the solidarity economy. – Tiffany Brown

Money is a resource that can be shared in community. Say you have $100,000 but you don’t need to use that money for 20 years. That $100,000 can be shared so that someone else, say an immigrant farmer, can acquire land. And then that resource gets returned over time, because the farmer is working that land, growing and selling food, having a livelihood for themselves. This also includes money that they would have been paying to rent that land, but now they own it instead, and have more stability. – Anthony Chang

3. Because the stock market is fundamentally extractive and exploitative and always has been.

People often default to what is supposedly “true” in economics – that money should make money off of money. People aren’t convinced that the stock market is the scariest monster in the room, that it is absolutely about extraction, exploitation, and it always has been. It was used to finance the slave trade, that’s how far back it goes. If you peel back all of the bullshit of what people say should be true in economics, and instead do economics of your heart and your spirit, it looks really different. – Tiffany

If you look at any large public corporation that is high growth, you have to ask – how did they do that? How does a Wells Fargo or an Exxon Mobil make billions of dollars of profit? Their profit margins are obscene. They’re overcharging and exploiting people in multiple ways to be able to generate profit for their investors. It requires a lot of willingness for people to face the reality of this exploitation and to consider what their money does and how that ripples out into the economy and into the community. I hope that people are willing to go on that journey. – Anthony

4. Investing can open doors for groups to access other money.

For many projects that are trying to build a structure for themselves that’s going to sustain them long term, some amount of debt is necessary. If they’re able to get debt in the form of patient and flexible capital from aligned funders, it opens doors for them to access public money or other private money from other sources down the line. It can be a really important stepping stone. – Nadav David

5. To do harm reduction around the assets of funders and donors.

Many of us started doing this work because we were doing climate divestment work, and the options for reinvestment were things like Chevron’s renewable portfolio or Coca Cola. That was untenable from a movement perspective! The contradiction of 5% of assets being given to movement organizations, and 95% of assets being invested in corporations was too much to stand. We have to think about our engagement from divestment to reinvestment, and put a wedge in what is typically just a transfer of assets within the same kind of ownership structure. We want to transform ownership within our economy. – Jen

And a note from Anthony on not becoming complacent, even when we’ve done harm reduction with assets: How do we avoid institutions investing in the solidarity economy and then feeling good enough about it that they don’t meaningfully redistribute? I see this in foundations where they take a surplus pot of capital they could give away, but instead they invest it. And then this inertia can set in like, hey, if I invested in worker owned co-ops and community land trusts and Black and brown communities, then I’m having the same impact. I should keep doing that, instead of actually redistributing this wealth that I don’t need. How do we avoid people feeling good enough doing the thing that’s not actually the thing that’s needed? – Anthony

6. To expand the sphere of influence of our social movements over capital that’s being held in public trust.

We spend a lot of time focused on how to influence funder’s and donor’s grants and giving, but our sphere of influence over grant resources is so limited. If our goal is to transform how resources are governed and who owns/benefits from our labor, land, and infrastructure in our economy, then how do we as the grassroots organizing sector and social movements actually contest for capital and power in larger ways? This question is what has led to foundation’s assets and donors’ investment portfolios becoming a target for social movements. It’s an opportunity for us to assert influence over and seek to align much the bigger forces of capital with our work and to potentially unlock some of these resources for community-owned and governed solidarity economy projects. – Jen

7. Because investing is a powerful tool in relationship with divestment.

Divestment is a call that is most effective when it’s tied to a larger movement and a set of grassroots campaigns or demands (see the Social Movement Investing report for more context). There is the potential for narrative and material impact when we have a really clear sense of what investing looks like and can be alongside the divestment. If we’re able to move resources out of extractive systems and into solidarity economy projects, I think it can ignite much more collective energy and excitement about investment. In this moment where people and organizations are wrestling with and taking action to divest from occupation, apartheid and genocide in support of Palestine, we must actualize the ways that divestment and reinvestment are directly connected to the solidarity economy we’re trying to build in the US and globally. – Nadav

8. So that BIPOC and working class communities can reclaim productivity in service of collective wealth building.

The phrase “productivity” is something I was politicized around by Ed Whitfield and Marnie Thompson (Seed Commons staff/board members). It’s about a community’s ability to produce and build wealth and have control of their material conditions in a meaningful way, so that they are no longer dependent on philanthropy. The investment piece is about how we work toward that goal of productivity, even while we still need to give and tend to a lot of the ways in which that’s not possible or people are struggling right now. That’s to me actually the tension between grants and investments. It’s not philosophical, it’s like, where can we actually build that productivity for communities and social movements to build wealth for themselves and have agency in that? – Jen

9. Investing can create a longer onramp towards giving.

Say you invest $100,000 in a project for a 10 year loan. That’s 10 years of changing people’s lives. At the end of that 10 years, you have proof of concept of the power of this capital, and when the loans are set to mature, there’s an opportunity to evaluate whether you need that money back. As a wealth holder, you’ve been without that $100,000 for so long, maybe at that point you can part ways with that money. It’s like a 10 year experiment of getting comfortable not having that money. – Tiffany

10. Typical grant cycles don’t provide enough capital for major projects like land rematriation.

Typical funders and donors, and particularly grant cycles, aren’t aligned around the really big, visionary dreams our movements have. In order to do major land transfers, rematriation, acquisition projects, we can’t just go for one grant per year. We needed a mechanism to leverage significant amounts of capital. That often looks more like the investment side of funding than the grant side. AND we really need funders and donors to shift their grantmaking practices, the level of resources they are willing to give to support projects (both grants and zero-to- low-interest loans), and the way they engage all of their resources in support of social movements. We can look to Kataly’s Restorative Economics Fund as a powerful example of a funder moving resources that are deeply aligned both in how they structure as well as the level of resources they are moving in terms of grants and loans to land-based projects. – Jen

11. Investment dollars can allow groups to build the muscle of collective governance.

There are increasing numbers of community controlled funds that have collective governance by folks that are directly in the community or folks in deep relationship to frontline communities of color. Boston Ujima Fund, Climate Justice Alliance, Right To The City Alliance, and many others are exercising the muscles of building the new, alongside fighting the bad. To do that, we need to be able to govern, and we need to have the room to learn and try things and make mistakes, and then adapt from those mistakes. Folks that are willing to put non extractive capital into these kinds of projects are providing a runway for groups to be able to practice governance, and we are going to need that in the economy we want. – Anthony

12. Because there is no simple answer or approach, and the tensions we’re working within are historical, massive, and coming from movement tensions.

For instance, a core tension in the reparations movement right now in the US is that a lot of folks are urgently wanting to redistribute wealth as part of reparations. And within the movement, there are solidarity economy practitioners advocating for an approach that actually makes those assets and resources productive over time, an approach that goes beyond providing a $25,000 boost in income or payment toward individual home ownership to one that seeks to build collective wealth and ownership. These long-standing historical tensions feel very connected and present in some of the conversations that feel thorny and hard with funders and donors about redistributing their wealth. There is an opportunity for a deeper assessment of how we redistribute wealth in ways that build new regenerative economic structures. – Jen

13. Because “give vs. invest” is a false binary.

Given the complex conditions we live in, there’s no one size fits all solution to these questions. I think the question is “what are the conditions or the types of structures in which investment capital can be useful alongside grants, and thereby, how do we organize funders to be in alignment with those needs?” – Nadav

Investing in Community Movement Commons

The story of Community Movement Commons in Boston illustrates some of the learnings we’ve been in together. A recent Chordata Cohort decided they wanted to create a $3M flow fund. They worked with three financial activists- Anthony Chang, Aaron Tanaka and Jessica Norwood- to distribute the funds. Aaron’s portion was earmarked to go to Community Movement Commons in Boston, which was about $885K in investment and $356K in grants. CMC is a visionary space in Roxbury, a Black working class neighborhood, that will house social movement organizations, a Black-led birth center that will provide a full spectrum of gender-affirming reproductive care, and a space for neighbors to gather, organize and build community.

The future Community Movement Commons in Roxbury, MA

The cohort’s contribution was originally made as an integrated capital investment, with a portion of it as grants and a portion as loans. The loan terms were as friendly as possible. When the project leaders took the design to the neighborhood and to community members, they got feedback that the footprint was too big and that it took up too much green space, and they felt strongly that the footprint of the building needed to be reduced. That meant that some of the uses of the building- a cultural space, a music space, some rentable office spaces- had to go. Given that these uses would have generated revenue, the opportunity for revenue decreased.

An image depicting the future birth center at Community Movement Commons

The organizers of the project spoke with the cohort and shared what was happening. They explained that debt totally made sense at the beginning, and that now the operating model was completely different upon getting the community’s feedback. The fact that the cohort agreed to give the project debt capital led to the project leveraging an additional loan, and also helped the project to get closer to their capital stack for a new market tax credit (a federal program that supports community development projects). It was a great commitment from the cohort, and so helpful! And, because of the changing plans for the building, it was now more difficult for the project to carry and pay back that debt. The organizers asked the cohort if they would be able to forgive the debt or turn it into a concessionary loan or a grant. And the cohort did!

The future site of Community Movement Commons

Jen, who was one of the people working on the project, shared: “Those of us doing the on-the-ground work of these projects, like organizing in neighborhoods, getting things figured out in terms of the design on the land and running the capital campaigns, we have to do a ton of work to align all those pieces in a values aligned way. And then we really need the funders and donors to stand with us and be in the same kind of relationship. It was so beautiful and powerful that this actually happened in this instance!”

Nadav is also involved in the project. He shared: “Initially in the project, having debt was a tool to organize other funders along the way. Funders who came to us and said, “We want to talk about debt with you”. We were able to say, “We’ll only talk to you about debt if it’s zero percent and patient, like Chordata is doing.” That was an important intervention. Chordata’s belief in the project and willingness to bring integrated capital made that possible. The more that we have real relationships between funders, investors, and the projects, the better, because we’re able to adjust and be flexible and ask for things that we need and to do it in a much more authentic way than the traditional relationships that funders have with grantees. This felt like a really beautiful example of how we could move together.”

Our most recent Chordata Cohort!

One of Chordata’s core invitations for wealth holders is to step into a practice of shared risk and accountability. We have to ask ourselves “What’s it gonna take to get to where we want to go?” It takes both a bet with your investment capital, it takes having skin in the game with your philanthropic capital, and it takes being in partnership over a long time horizon.

Thank you to our friends Anthony Change, Nadav David, and Jennifer Near for lending your brilliant thoughts to this blog post!

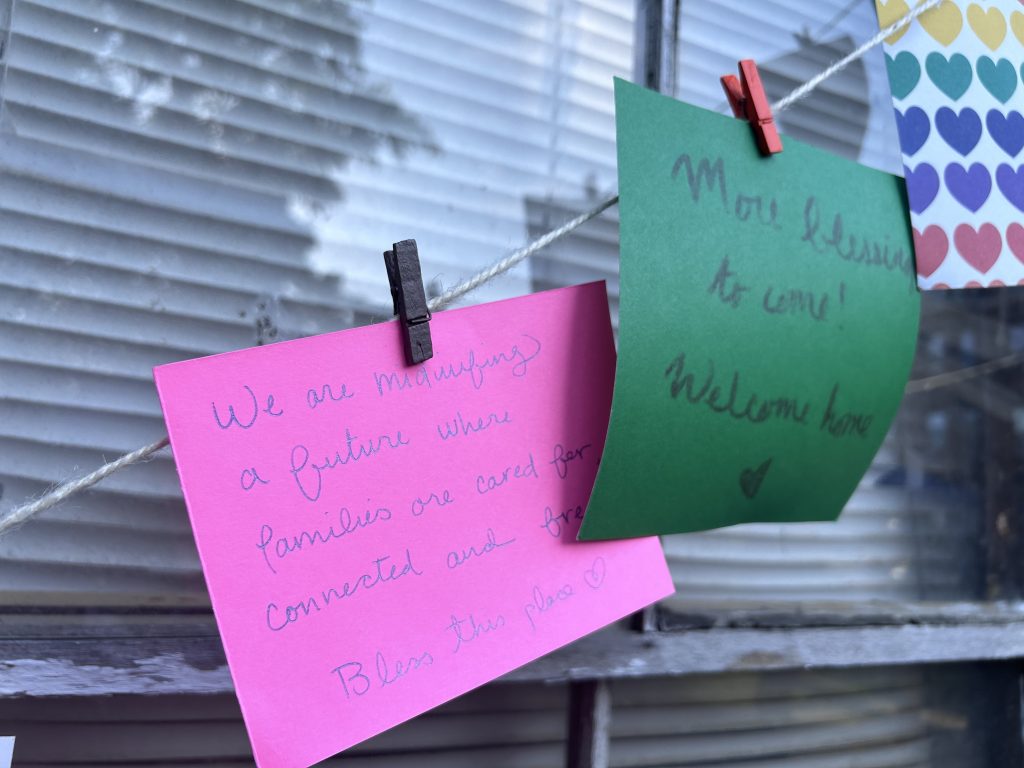

Blessings posted at the Community Movement Commons. One reads “We are midwifing a future where families are cared for, connected and free. Bless this place <3”