By Tiffany Brown

I recently returned from a delegation to Emilia-Romagna in Italy and the Basque Country in Spain, organized by the Center for Cultural Innovation. Their initiative is called Reimagining Scale, and brought together a group of US-based solidarity economy practitioners ranging from academics to organizers to investors. Emilia-Romagna is a region in Italy with a robust cooperative sector that is decentralized and decades old, and Bilbao, in the Basque Country, is a region that has a highly centralized, established cooperative economic system. Our intention was to learn more about the enabling characteristics that have led to these two thriving regional cooperative economic systems, and to consider what would be needed to scale the movement here in the United States.

Emilia-Romagna in Italy

There were 16 of us on the trip, and participants ranged from Jessica Gordon-Nembhard, who wrote Collective Courage, to Dr. Ebony Edwards from Neighbor Built – described as “the Black Mondragon”. Some of our close colleagues also joined – Nia Evans from Ujima, Noni Sessions from EBPREC, and Anasa Troutman, who purchased the historic Clayborn Temple.

Our group outside of Villa Albareto – a balsamic vinegar producer in the Modena region of Italy

BOLOGNA

We began our trip in Bologna, in the Emilia-Romagna region of Italy, learning about cooperatives. We toured a Parmesan cheese factory which is a producer cooperative. I’ve never seen so much cheese in my life! The cooperative members are dairy farmers who pool their milk to meet the volume needed to go to market. It’s a good example of how a cooperative doesn’t have to be inherently radical—sometimes it’s just a practical way to stay competitive.

Touring a parmesan producer cooperative

We visited the Modena region, where they make traditional balsamic vinegar. The vinegar is aged in barrels kept in people’s attics. It’s a deeply artisanal and cultural practice. When a child is born, families often start a barrel for them, and after 25 years of careful aging, it’s given as a legacy gift when the child starts their own family. Because there’s not a huge market and the process takes decades, these artisans formed a cooperative to pool resources. As I was in the home of one of the producers, sipping on heavenly samples of balsamic, what struck me was how cooperatives can support not just artists, but also cultural traditions. These are legacy products. You won’t be surprised to hear I brought back a couple of bottles!

Balsamic vinegar aging in a producer’s attic

We ended our time in Italy with Emil Banca, a cooperative bank which operates like a credit union. They understand their work to be in service of the people, and they use the language of mutualism and intercooperation. I asked a question about their interest rates—because, in contrast to the U.S. banking system, which often profits off of poor people through fees and high lending rates—they were deeply community-oriented. On one loan they were charging less than 3% interest, and 5% interest is the maximum they charge a borrower, depending on duration and risk. These rates really underscored to me how different their approach to capital is!

Outside of Confcooperative in Emilia-Romagna

MONDRAGON

Next, we headed to Bilbao, Spain. I’ve never flown into a more beautiful place—lush, green farmland, and Bilbao itself is a gorgeous city with the iconic Guggenheim museum and the Nervión river running through the center of the city.

The Nervion river in Bilbao

Having heard about Mondragon for years, I was really looking forward to this part of the trip. Mondragon is a global leader when it comes to scaling a cooperative economy and truly serving the people of a region.

Mondragon defines itself as “a dedicated group of people with a cooperative identity forming a business group that is profitable, competitive and enterprising, and capable of successfully operating in global markets. Our organisation uses democratic methods in its corporate organisation, and its aims are employment, the personal and professional advancement of its workers, and the development of its community.”

The scale of the cooperative is absolutely visionary. Organizationally, Mondragon consists of 81 separate, self-governing cooperatives, which employ 70,000 people. They have 12 research and development centers, occupying first place in Basque region business rankings and tenth in Spain.

Learning from Ander at Mondragon

When we arrived, we were met by two women – Kaisu Tuominiemi and Amaia Castañeda Urrestarazu- who would become our hosts for the rest of the trip. Kaisu is Finnish and Amaia is Basque. They run a cooperative incubator called TazeBaez that works alongside Mondragon University to support the development of entrepreneurs who may eventually become part of the Mondragon ecosystem.

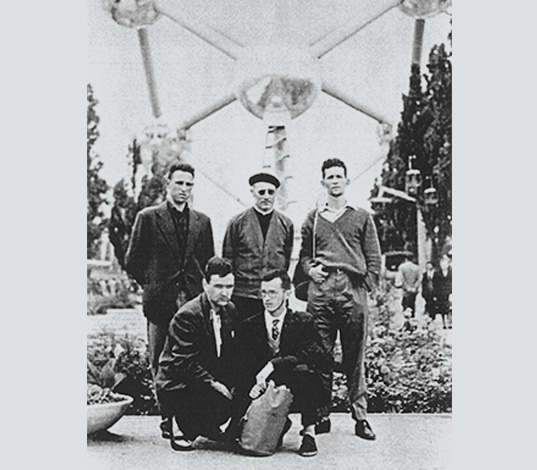

Our first stop was the Mondragon headquarters, which are housed in a gorgeous old castle in the hills outside the town of Mondragon. We were greeted by a man named Ander, whose sole job is to share about Mondragon’s work. Ander walked us through the history of Mondragon’s formation. The cooperative began after the Spanish civil war, when a priest named Father Jose Maria Arizmendiarrieta encouraged a group of young people to leave the factories they were working in and to start their own company based on the principles of worker’s democracy.

Outside of Mondragon’s headquarters, called Otalora

It was powerful to understand the historical conditions that allowed for the flourishing of this cooperative economy – it was the aftermath of the war, unemployment was high, and the economy needed to be rebuilt. In that moment of crisis, a leader with a specific theory of change, rooted in faith, was able to help people see a new way forward. Father Arizmendiarrieta communicated his vision using popular education. They were trying to spark cultural resistance—and it took shape in a beautiful way that led to the creation of a strong cooperative model. Early on, they were committed to including women in the cooperative and in education programs, and they faced backlash from the Spanish government through banning cooperative members from participating in social security. In the face of this repression they quickly set up their own structures for providing social support to their people.

Father José María in 1958, along with lecturers and students from the Escuela Profesional

We visited the TazeBaez site, where Mondragon University has some of its offices. There, we met entrepreneurs and got to see the efficient cooperative machine that is Mondragon. They’re serious about efficiency and doing good business! Contrary to the context of US capitalism, their work is all aimed at benefiting the Basque people, who are a historically oppressed group within Spain. Mondragon shows that a cooperative can be a serious, viable model.

One of the things I loved learning about Mondragon is that they have a formula for sharing wealth while staying competitive. Within each of Mondragon’s 13 sectors, no one can earn more than six times the salary of the lowest-paid employee, and each sector is bound by the principles of intercooperation. If one business in a sector is struggling, at the end of the year when everyone balances their books, all the other businesses in that sector pool their resources to make it whole. This way, no one ever fails, because the whole is more important than any one part. Each business contributes about 15% of their income to Mondragon, which goes to things like capital accounts and future retirement. Then from what’s left, portions are allotted to the workers, community well-being, and research and development.

The gorgeous hills of the Oñati region, Basque Country

SAN SEBASTIÁN

The following day we went to San Sebastián, a gorgeous city in the Basque region, known for their gastronomic societies called Txoko (pronounced “cho-ko” and meaning “small corner”). The remarkable feature of the txokos is that they are like a neighborhood restaurant, but they use a totally cooperative model in which the members themselves do the shopping and cooking—and the eating, of course! Everyone contributes money toward supplies and upkeep costs. These gastronomic societies are members-only, and they offer a reason to get together with friends and family over food, keeping Basque recipes, language and culture alive.

Members of our group enjoying a meal together

We had lunch at a txoko—what a privilege, as non-members!—and ate a delicious meal of tomato salad, local guindilla peppers (which can be quite spicy!), and bonito tuna. There’s a short window when the tuna moves from the sea into the Atlantic, and they harvest it then. And, of course, there was tons of wine and conversation! We got to eat with people from the TazeBaez community. Our group was mostly Black women from the U.S., and the TazeBaez community is mostly Basque. Though we come from very different contexts, we have the shared experiences of oppressed identities and a shared commitment to building liberatory cultures, economies, and communities.

RESOURCING THE RELATIONAL INFRASTRUCTURE FOR A NEW WORLD

The trip offered a truly immersive experience inside of a solidarity economy. Latin American solidarity economy practitioners often use the word conviviality—the idea of doing and being, for the simple pleasure of being together. To them, that’s what life is: eating, laughing, drinking, talking, building.

Having a meal together in San Sebastian at a cafe/bookstore that hosted our group for dinner

I loved the cooperatives’ clarity around the principles of mutualism and intercooperation. Being on this trip with people like Noni from EBPREC and Nia from Ujima reminded me that our success is bound up with theirs. We’ve always felt that reciprocal relationship, but what if, over time, we built up infrastructure so we were truly engaged in intercooperation? Shifting our mindset from: “we invest in them and do our best to support them” to: “If they fail, we fail.” That orientation offers a different starting place from which to think about the kind of infrastructure we need in order to ensure we have stable footing as we leap into building an economy that works for everyone.

I started thinking more about the idea of a bank. Mondragon has created an elegant loop: They needed to finance cooperative work, so they built a bank. People deposit money in the bank, and that money is recycled throughout the solidarity economy. It helps scale businesses and take care of the people. Could we collectively have something like that here in the US—a depository institution that not only keeps our money safe but also loans it out within the solidarity economy? One that helps build collective wealth and well-being for our people?

Noni Session (a group member) and Chris Audain (one of our group leaders from CCI), deep in discussion in the Oñati region.

We discussed this on our final day. We were all trying to understand our relationships to one another, and someone said: “We don’t have a backbone.” That really struck me. We don’t always refer to the meaning of our business name (Chordata references animals with a backbone), and it was powerful to hear that language. Mondragon’s backbone, the thing that’s kept them a viable global competitor, is their banking system.

So now I’m wondering: who among us is going to start a bank?

The transformative power of the trip wasn’t because we were being facilitated through exercises or conversations together (though those were incredible!)—it was the relational infrastructure that we were able to build. Angie Kim, the leader of CCI, articulated her commitment to the trip as not just a way to “go learn about cooperatives,” but to resource the relational infrastructure needed to build a new world.

I feel deeply connected to this group of 16 leaders now, after traveling together into what felt like another reality – one in which solidarity shapes almost every aspect of life. I’m so grateful to the people who we met on our travels, who are so many steps ahead of us in building a formidable solidarity economy. Now our mandate is to figure out: What are we going to build here at home, while embodying a spirit of conviviality?

Our group after visiting a cooperative where we had lunch in Emilia-Romagna